The Imperfect Global Tax Answer

There are a lot of outstanding questions on the OECD's global minimum tax plan, but they don't necessarily all need answers.

A surprisingly large portion of the international tax debates raging around the world today come down to one question–is the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act working?

That sounds like either an easy-to-answer question, or one that should be confined to U.S. political debates. But since key provisions of the TCJA became the basis for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s 15% global minimum tax plan, it’s not just a U.S. issue anymore.

And how the U.S. fits into the global plan could also determine its ultimate outcome. So this isn’t just an issue for the 2024 presidential primaries, or D.C. tax wonk panels.

There are two competing narratives about the TCJA’s international tax framework, which is maybe the most dramatic way the law overhauled the entire tax code.

One is that it’s a farce. The law exempted most overseas income from taxation–a huge surrender and giveaway to corporate multinationals–and put in only toothless anti-abuse rules to stop taxable income from rushing offshore. In particular, the 10.5% tax on global intangible low-taxed income, which is supposed to target the low-taxed income of U.S. taxpayers, allows companies to aggregate their foreign earnings to shield continued tax avoidance. Corporations can still use complex tax maneuvers to place income in low-tax jurisdictions, so long as they’ve got enough other income in high-tax jurisdictions (which they normally would anyways) to offset and arrive at a 10.5% rate. Only by conforming the U.S. to new global norms set by the OECD will we truly put a dent in base erosion.

The counter-narrative is so dramatically different, it seems like it’s in an alternate reality. According to the law’s defenders, the TCJA has all but ended corporate tax avoidance, at least by U.S. multinationals. By putting in place the world’s first true minimum tax, the law has effectively eliminated incentives to locate income in low-taxed, low-substance jurisdictions. What looks like evidence of continued profit-shifting is actually just the remnants of the prior system, like the twinkle of an exploded star whose last light has yet to reach Earth. True, the TCJA exempted offshore income, but this just recognized the reality of the prior system's indefinite offshore deferral. (And it brought us closer to how the rest of the world taxes corporations on a territorial basis.) Rather than a loophole, GILTI’s use of aggregation–which is counterbalanced by many other restrictions such as the lack of net operating loss and foreign tax credit carryforwards, and the exclusion of loss-making entities–is a sensible way to give companies some needed flexibility, and to avoid penalizing them for inadvertent unusual years. And by maintaining an overall minimum tax rate, it ensures that the law stays focused on U.S. base erosion, without capturing foreign-to-foreign profit-shifting that shouldn’t be a priority for the U.S. Treasury Department.

So far, there's frustratingly little evidence to litigate these contradictory views. (The IRS data from country-by-country reports only goes up to 2020, for instance, three years after the TCJA enactment.)

In GILTI’s defense, the law was attractive enough that other countries wanted to add it to the OECD’s global tax project. But they also ultimately decided to make it a country-by-country system, avoiding the aggregation that critics claimed undermined the U.S. law.

What’s funny is that as huge as the divergence between these two views seems, it may not end up mattering that much.

The more countries proceed with enactment of the minimum tax, the more the results of an aggregated or country-by-country minimum tax regime will narrow. If this really is about foreign-to-foreign profit-shifting (from the U.S. perspective), then the opportunities for U.S. companies to engage in this sort of tax planning will dissipate regardless of what Congress does.

Take the recent news that Bermuda is considering implementing a domestic 15% minimum tax. Will the rest of the Caribbean follow suit? If most of the countries that companies’ previously used as a destination for income raise their rates to 15%, then the GILTI aggregation will hardly matter.

Of course, almost certainly, somewhere, there will still be a tax haven. In theory, a U.S. company could shift all of its income to one of the few remaining low-tax jurisdictions, at such a proportion that it’s still offset by its other income for GILTI purposes. That’s how it might work if tax avoidance were completely frictionless and costless. But in the real world, tax planning involves tradeoffs, and fewer destinations will likely mean fewer opportunities. (Putting aside the OECD enforcement rules like the under-taxed profit rule for a second.)

One thing to keep in mind is that these rules are supposed to be backstops laid on top of the existing transfer pricing system. That means they’re not necessarily trying to be perfect. Would ending all profit-shifting and tax avoidance really be worth the huge administrative costs, or is there somewhere a point of diminishing return? As I understand it, the main goal of a minimum tax in this context is to relieve the pressure on the existing system by dramatically disincentivizing opportunities for base erosion. Those disincentives can be achieved without necessarily taxing all income at whatever we deem the right rate to be.

If the current global tax landscape ever reaches an equilibrium, it’s likely to be very imperfect one. As it stands now, the OECD UTPR will continue to hit U.S. tax incentives and remain a source of political and diplomatic tension--even if the system silently works to block current forms of tax avoidance on both sides of the Atlantic.

Maybe the countries will eventually recognize this and come to an agreement that accepts a more intertwined co-existence with GILTI.

But if Congress won't eventually act, everyone will have to deal with its incongruity to the OECD’s global regime. However imperfect the results may be.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

A message from Exactera:

At Exactera, we believe that tax compliance is more than just obligatory documentation. Approached strategically, compliance can be an ongoing tool that reveals valuable insights about a business’ performance. Our AI-driven transfer pricing software, revolutionary income tax provision solution, and R&D tax credit services empower tax professionals to go beyond mere data gathering and number crunching. Our analytics home in on how a company’s tax position impacts the bottom line. Tax departments that embrace our technology become a value-add part of the business. At Exactera, we turn tax data into business intelligence. Unleash the power of compliance. See how at exactera.com

Thank you for reading! If you're not yet a subscriber, please consider signing up for a free subscription.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- The long-awaited text of the multilateral convention to implement Amount A of Pillar One–a key new plan from the OECD to allow countries to capture more income from transactions in their markets–was finally released Wednesday. According to the OECD, the document reflects the “current consensus” among all of the 143 countries involved in the project. If that sounds a bit shaky to you, well, you’re onto something: there are many objections from some countries on particular provisions, noted in the footnotes. Officials have described these as minor technical matters, but some seem to verge into policy questions. The issues include how to consider withholding taxes (which are technically separate but often considered “in lieu of” income taxes), a safe harbor for marketing and distribution, and effective start dates. Interestingly, many of the objections are from Brazil and India, two of the biggest markets that would be involved in the new regime. Nevertheless, this is another sign of progress in the project, which could convince countries to stick to an agreement to hold off on new digital services taxes until at least 2025. But the pressure for the OECD to show a real agreement on language will only increase from here on out. Wednesday’s release includes not only the text itself but a 600-page “Explanatory Statement,” an “Understanding on the Application of Certainty of Amount A,” and a progress report to the G-20.

- Also released by the OECD on Wednesday is the Minimum Tax Implementation Handbook for Pillar Two, a brief outline of issues for jurisdictions to consider as they enact and implement the Pillar Two framework. This doesn’t cover much new ground but will likely be helpful for tax officials and lawmakers as they try to tackle this complex new regime. One point the document underscores is that if a jurisdiction enacts all of the Pillar Two provisions, including the domestic minimum tax, it may also need to change pre-existing tax incentives to avoid excessive administrative burdens and confusion for international investors.

- Tensions over digital services taxes here in North America continue to broil, at least on one side of the northern border. The top senators for the Senate Finance Committee released a letter sent to the United States Trade Representative, blasting Canada’s proposed 3% levy on revenue from online transactions. This follows a letter from members of the House Ways and Means Committee, which was sent to the USTR as well as Treasury. The Senate letter is rather vague on a point of action, but asks for USTR Katharine Tai to “make clear that your office will immediately respond using available trade tools upon Canada’s enactment of any DST.” So far, the administration hasn’t made any concrete actions against Canada’s planned DST, but given this political pressure–and Canada’s apparent unwillingness to reconsider–it may only be a matter of time.

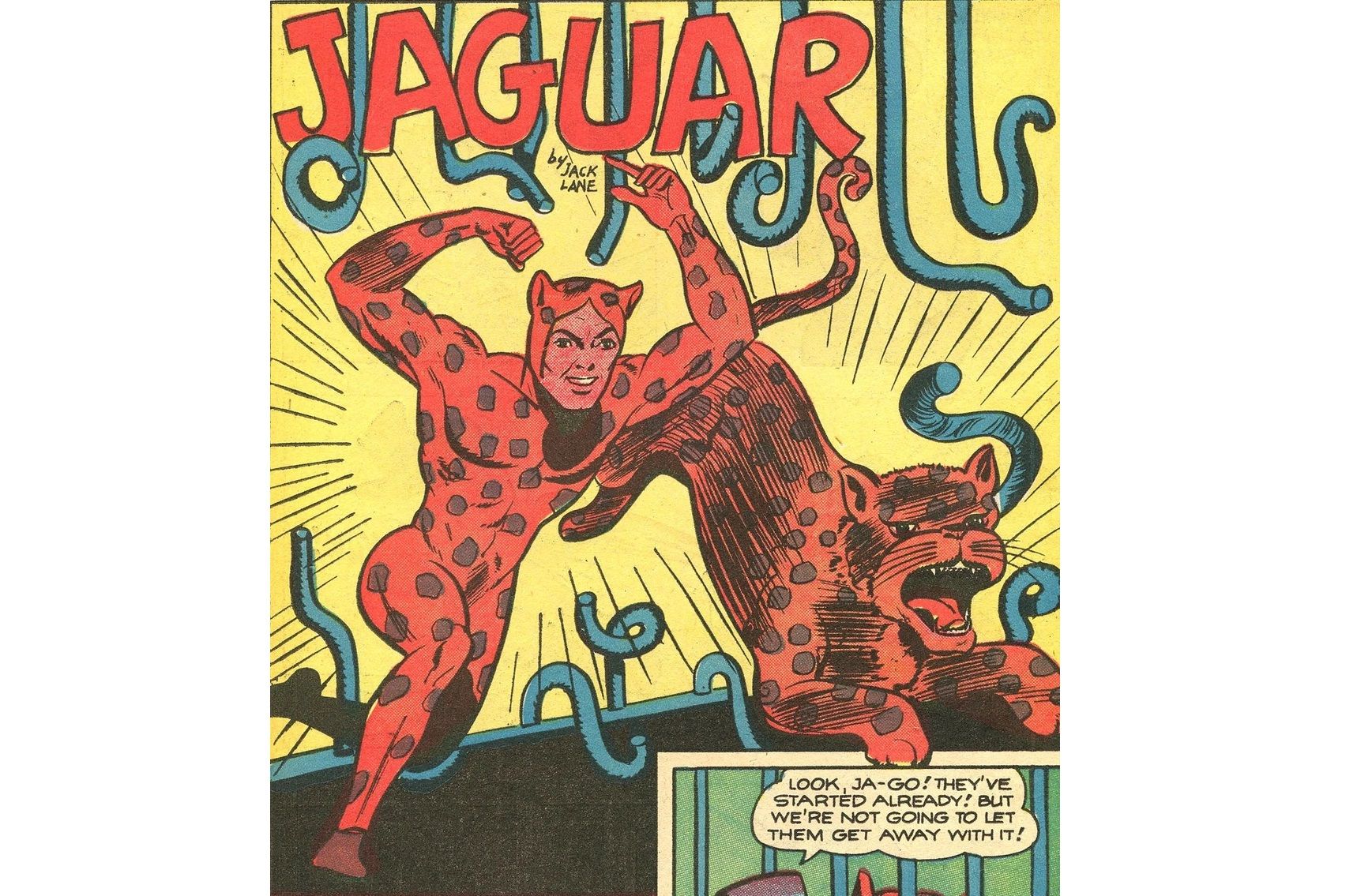

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Every week, a new character from the Golden Age of Superheroes who's fallen out of use.

Jaguar Man, first appearing in All Great Comics #1 in 1945. For unexplained reasons, he can communicate with panthers of all kinds while possessing big cat-like powers himself. He also is assisted in crime-fighting by his pet jaguar, who is sometimes named Ja-Go.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.