Bidenomics' Tax Conflicts

President Biden sees "Bidenomics" as a winning economic message–here are some of the questions it raises about tax policy.

With inflation calming down and the economy looking up, President Joe Biden is increasingly staking his re-election hopes on “Bidenomics.” The term plays on “Reaganomics,” and Biden claims it offers an alternative to supply-side economics–the "trickle-down" theory--that have dominated the Republican agenda for decades.

Rather than holding blind faith that reducing taxes will fuel growth, Bidenomics seeks to rebuild the economy from the “middle-out,” through robust government investments in domestic manufacturing, including the green energy industry of tomorrow.

Taxes are a big part of the Bidenomics pitch. In speeches, Biden doesn’t just blast Republican proposals to lower tax rates–he also condemns “loopholes” that allow giant corporations and billionaires to avoid paying the full amount of taxes they owe at the current rates. Or so he says.

“I think we all know: Nobody, including those who would do very well but aren't super, super wealthy -- nobody thinks the tax code is fair,” Biden said at a campaign speech in Philadelphia in June.

To summarize in a sentence, Bidenomics is about ensuring that corporations and the rich pay their “fair share”–a term that always makes tax experts grimace–and reinvesting the proceeds directly back into the economy for the benefit of workers.

As campaign rhetoric, it paints a vivid picture and contrast with the business-friendly populism of the Trump-era GOP. But as the actual policy plays out, nuances and tensions (if not outright contradictions) are revealed.

The two parts of the equation–ensuring that companies pay the right amount of taxes and reinvesting in the economy–conflict with each other more than you might think.

While Biden can be unsparing in his criticisms of big business, his environmental and manufacturing policies count on corporate America to be a partner. The entire premise of the Inflation Reduction Act is that companies will jump at the new lucrative incentives to invest in clean energy production. His strategy here recalls Franklin Roosevelt, who excoriated the rich during the Depression and became persona non grata among businessmen for his New Deal policies, but quickly turned to them for the production of arms during World War II. While Biden wants to see businesses properly taxed (however that’s measured), he’s not against helping them do very well as they do the good work of decarbonizing the economy.

It’s also not a huge surprise that the IRA also depends on the tax code to dole out most of these new goodies. The government has long used taxes to incentivize certain behaviors from individuals or corporations–mostly out of convenience. Whether or not it makes sense as pure policy–and there are some reasons why outright subsidies may be preferable–in terms of administrative ease and practicality, the tax code has a lot of benefits. There’s already a vast and time-tested system in place to collect income from companies, it’s easy enough to turn the switch the other way. And there's a pre-existing regime for business tax credits that can easily accommodate more.

The problem is that a “loophole” allowing tax avoidance and a tax incentive enacted for noble goals aren’t always easy to distinguish.

Take the corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT or “camtee”), that was also enacted by the IRA. The tax is meant to target companies with low effective tax rates–the companies that Biden often targets in stump speeches, for achieving low or negative effective tax rates on skyrocketing profits. Those companies are identified through profits reported on financial accounting statements, which can differ from taxable income. That’s why the tax payments can appear so low. The corporate alternative minimum tax also uses financial accounting data as a basis for the 15% rate it applies.

But to get it through Congress, lawmakers ultimately exempted many of the reasons why those companies get to such low rates. Credits for research and development, a huge factor for many of the country’s largest tech firms, are partially excluded in the calculation. Accelerated depreciation, the ability to expense certain investments closer to when they’re incurred–thus leading to exceptionally low tax payments for costly years–were also taken out to help achieve Sen. Kyrsten Sinema's support. Maybe that’s not part of “Bidenomics” but it’s in keeping with the general idea, to retain incentives tied to spending and investment.

That left mainly deductions for stock-based compensation, which can also often lead to wide disparities between taxable income and financial accounting profit. That may not seem like a very sympathetic deduction, although it has its defenders. It’s also likelier to be used by companies in the tech sphere when they’re spending on new products and initiatives.

The result of these various carveouts was a new tax regime that is much more uneven and narrow than it was originally intended, and is faced with a plethora of administration challenges.

Of course, there’s also the OECD’s 15% global minimum tax, which was strongly supported by the Biden Administration but not enacted by Congress. Presumably it’s part of the Bidenomics philosophy–ensuring the fair payments of taxes by all–but it’s also run into its domestic priorities.

While the U.S. hasn’t implemented the plan, other countries can use the OECD minimum tax as the basis for taxing American companies, through the under-taxed profits rule, part of the agreement’s enforcement mechanism. The UTPR kicks in if a company’s effective tax rate falls below 15% in any jurisdiction, including the home of their parent company. Reasons that it may do that in the U.S. include the use of credits for research and development or green energy production–even some of those enacted through the Inflation Reduction Act. (Weirdly enough, the OECD policy does exempt stock-based compensation, both through the favorable calculation of income as well as a substance-based carveout for payroll expenses.)

For a while, it looked like two major administration accomplishments–the IRA spending on climate change and the OECD agreement–could cancel each other out. They were ultimately able to finesse the rules to achieve better treatment for most–but not all–of those IRA incentives. But it’s not a total solution. Those credits count as new income in the OECD calculation, still decreasing the recipient’s effective tax rate somewhat. It's just not as much as if they had counted as an outright reduction in taxes. The treatment also comes with plenty of restrictions and caveats.

So far, the OECD and Treasury haven’t been able to come up with a solution for R&D credits, however. Companies that claim them in the U.S. could see increased taxes in other jurisdictions participating in the global minimum tax, negating some of their value. That doesn’t seem like a result that’s consistent with the philosophy of Bidenomics, to reward investment into growth and innovation in the U.S.

Part of this has to do with the broad way that the OECD plan was designed, which in part sought to end the “race to the bottom,” a goal also touted by the Biden Administration. That refers to tax competition, the pressure that smaller countries often face to reduce tax rates in the hopes of bringing in investment. But how is that so different from the IRA’s tax incentives?

Looking forward, President Biden has proposed a “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax,” that is a somewhat similar concept to these other minimum tax regimes. It taxes households worth over $100 million at 20%, but includes other forms of income such as unrealized capital gains. This could help reduce the current tax system’s bias towards assets over income, while avoiding some of the constitutional questions about a wealth tax. But it will also re-open the debate on whether reducing the current favorable treatment for capital gains would discourage investment and saving–perhaps not fully in keeping with Bidenomics’ philosophy of vigorous support of the economy (and making sure the money stays in the U.S.)

This all shows the resiliency of an age-old concept in tax policy, that one person’s loophole is another’s valued and sensible tax incentive. (As Sen. Russell Long put it a half-century ago, a loophole is when it benefits the other guy. “If it benefits you, it’s tax reform.”)

But it also demonstrates the drawbacks in a tax policy approach that looks primarily at results, rather than causes. The CAMT seems to come from the philosophy that it’s wrong for a company to ever have an abnormally low effective tax rate, even if we approve of all of the policies that achieve it. That may sound sensible at first blush, but it means that various incentives count for more or less depending on a taxpayer’s circumstance, something that gets messy in practical policy. As we’re seeing.

This isn’t just a Bidenomics issue. The OECD’s plan primarily targets jurisdictions with low effective tax rates and few indicators of economic substance, and it’s partially modeled on the U.S. tax on global intangible low-taxed income, which works the same way. (That was enacted by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, to show that this is to some degree a bipartisan philosophy.)

After years of trying to fine-tune the rules on the pricing of valuable intangible assets like intellectual property–often used in tax avoidance structures because of their mobility and difficulty in valuation–tax policymakers at all levels decided that more blunt rules were needed to block their use. If you stop the big drains on taxable income, maybe the underlying rules will be easier to carry out.

There are many appeals for this approach, but lawmakers (and politicians running for re-election) need to consider their downsides as well.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- Speaking of the Inflation Reduction Act, the White House is commemorating its one-year anniversary, touting what it claims are many signs that it is already working. This includes many initiatives from the Internal Revenue Service, thanks to the $80 billion boost in funding included in the IRA. Treasury said new enforcement efforts identified 100 individuals who are “claiming benefits in Puerto Rico without meeting the residence source rules.” Many of these will result in criminal investigations, according to the statement. The agency is also working to clamp down on pension arrangements that, it claims, manipulate the U.S.-Malta tax treaty. These are all part of a new focus on tax evasion by high-income individuals through this enhanced enforcement funding.

- Speaking of the OECD’s global minimum tax, Australia, Finland and the Czech Republic all announced steps this week to implement the rules. This follows Canada’s recent unveiling of draft legislation, which it aims to pass this year. In Australia’s case, their tax authority has begun targeted consultations with industry groups as well as “mid-tier firms.” This dynamic–with countries rapidly moving ahead with legislation while the OECD still irons out the rules and U.S. politicians bolster their opposition–could cause some disconnects in the months and years ahead.

- And speaking of Australia, the country’s minister for climate change and energy announced Tuesday that his department was reviewing options for a carbon border adjustment, similar to the European Union’s, to address “carbon leakage” and whether it will undermine Australia’s decarbonization goals. As I’ve written, this is sure to become one of the primary international tax issues of the future as countries seek to ensure that their progress in reducing fossil fuel use isn’t negated by less proactive nations.

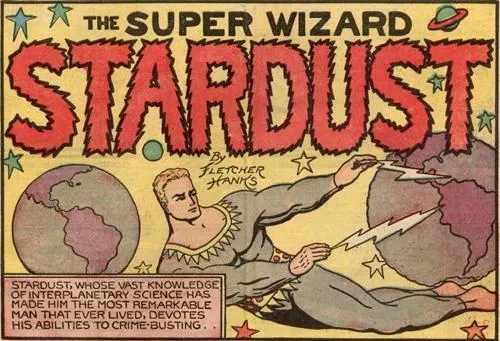

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Stardust the Super Wizard, appearing first in Fantastic Comics #1 in 1939. "The most remarkable man that ever lived," Stardust lives on a "private star" and flies through space with his "tubular spatial accelerated supersolar light waves," battling evil-doers across the galaxy. He comes to Earth and uses his abilities and nearly unlimited technological powers to stop a team of presidential assassins and fight other assorted spies and terrorists. He also defeats intergalactic fiends such as Kaos, who he turns into a worm, and the Demon, who has a powerful earthquake machine.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.