The Democrats' Tax Dilemma

Many Democrats think Kamala Harris could have won if she leaned more into populist themes. Should she have talked more about taxes?

While maybe not shocking, Donald Trump’s return to the White House is so surreal, it’s sent Democrats on a mission of soul-searching and grasping for answers in the months that followed. How did this happen?

Party operatives, activists, commentators and Democratic campaign staff have engaged in a war of words across the Internet about what went wrong–and whether Democratic Nominee Kamala Harris went too far to the left or or to the right.

In less binary terms, the debate has centered on whether Democrats have become too associated with “woke” ideology out of step with voters, or if they needed to do more to tap into the populist rage that seems to still be simmering nearly a decade after Trump first won in 2016.

These aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive.

I have plenty of thoughts about all of this. But for the purposes of this newsletter, the “populist” angle provokes an interesting question. Democrats have long decried the state of the corporate tax system, claiming it fails to raise enough revenue because many of America’s biggest companies aren’t adequately taxed.

These themes weren’t prominent in Harris’ campaign, however. When she touched on taxes, it tended to be to highlight Trump’s own proposals, such as extending the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and enacting new tariffs.

Should she have leaned in harder on themes of toughening corporate taxation and ensuring that corporate giants pay their “fair share?” Could that have negated some of Trump’s populist edge and helped her to victory?

These issues were a regular refrain for current President Joe Biden, both during his 2020 campaign and in the years that followed. During his 2020 Democratic National Convention speech, he claimed that many of the largest corporations “pay no tax at all,” and decried the notion of a “tax code that rewards wealth more than it rewards work.”

“It’s long past time the wealthiest people and the biggest corporations in this country paid their fair share,” Biden said.

This translated into policy during his presidency. With Biden’s prodding, Congress included a 15% corporate alternative minimum tax in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, designed to hit companies with unusually small effective tax rates measured against profit in financial statements. He also pushed for a final agreement in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Two-Pillar project, elevating the proceedings to a heightened level of political attention and touting the proposed 15% global minimum tax as a major accomplishment.

International corporate tax issues played a small but clear role in the 2016 race, as well. Both candidates mentioned the rush of corporate inversions in the years prior. (Which the Obama administration issued regulations to halt that same year.)

In Trump’s case, this was to demonstrate the problems with the U.S. corporate tax, and why he should be elected to overhaul it. His infamous decree, “I alone can fix it,” was specifically about the tax system.

In contrast to Biden, Harris’ sole mentions of taxation in her 2024 convention speech weren’t about the current tax system, but the changes her opponent was promising to make, that she found unacceptable. In particular, she focused on the universal tariffs he’s vowed to put in place, possibly through executive action, calling them a $4,000 per year “national sales tax.” (For whatever reason, this never seemed to land with voters–my theory is that on its face it sounded too outlandish to be a real policy.)

In stump speeches, Harris would often include a throw-away line about increased taxation of the wealthy, conflating corporate and wealth taxation into a single issue. But it never became a dominant or even significant part of her pitch to voters.

Public polling on this paints a mixed picture. Seventy percent of Americans believe corporations are taxed too little, a figure that pretty much hasn’t budged for years. On the other hand, about 50% of Americans are satisfied with the amount in tax they pay, and the numbers also suggest that taxes aren’t voters’ primary concern as they deal with higher consumer prices and higher interest rates.

International tax issues have always registered a bit differently in the U.S., than elsewhere in the world–especially Europe. Americans may view tax-dodging as morally wrong, but with a national debt that’s skyrocketed to inconceivable proportions anyways, it all seems a bit abstract and removed. Whereas the push for stronger taxation in Europe arose as austerity measures were put in place after the 2008 financial crisis, creating a sense that companies with low tax payments were stealing vital services from regular citizens. People always respond more strongly to things that affect them, and perceived tax avoidance created a visceral reaction in Europe which has normally been absent on this side of the pond.

Even if Harris and the Democrats had wanted to emphasize corporate taxes more in this election, they might have found it difficult. Things have changed since 2016 and today, and the politics of this issue have become more complex, enigmatic and unpredictable. This will become all the more true as Trump focuses on his tax agenda for the next few years.

Before the major reforms enacted by the OECD in its first Base Erosion and Profit Shifting project as well as those in the TCJA, the narrative about corporate taxes was clear. The rules were outdated and ineffective, allowing companies to spin out elaborate structures like the “Double Irish” and build up offshore earnings free from U.S. taxation. This was especially true in the tech sector, reliant on valuable intangible assets like intellectual property, and earning billions of dollars through online transactions conducted without the traditional physical markers.

Now the picture has changed, but it’s still not exactly clear how. The OECD reforms have given countries additional tools to go after stateless or low-taxed income, and the potential for audit or publicity risk has made companies much more reluctant to create new structures. And the TCJA enacted the world’s first global minimum tax, the tax on global intangible low-taxed income, creating a significant disincentive for the use of low-tax havens.

I always thought it was curious that Trump himself never touted this aspect of the TCJA, despite his brand of being strain of populist conservatism that doesn't always valorize the corporate sector. Democrats, obviously, have never acknowledged that parts of the TCJA may be working, and maintain that GILTI’s aggregation of tax rates makes it fatally flawed. GILTI may be a rarity in DC–a success without a champion.

Though few would call GILTI an unqualified success. Some companies–especially in the pharmaceutical industry–continue to hold offshore earnings and enjoy low effective tax rates. But there are also many tech companies which have repatriated IP and seem to be responding to the TCJA incentives. Cases of clear, obvious tax avoidance are declining. It may be that, after years of these issues occupying the front pages and causing anxiety at the C-suite, international taxes have gone back to what they were before–a niche, in-the-weeds topic.

Democrats have also enacted reforms, including the 15% corporate alternative minimum tax. While it’s not likely not put an end to companies with years of zero taxation, it does complicate the story further. Democrats were not able to pass their proposed changes to the international tax rules during Biden’s term, something its officials sometimes describe as unfinished business.

That’s something to run on–but enacting those changes likely wouldn’t raise that much in revenue, suggesting that it’s not as big a problem as many assume. (And the potential revenue haul continues to dwindle as other countries enact the policy themselves.) The fact that it was a Democratic senator, Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who struck that portion of the Build Back Better Act from the final legislation also complicated the messaging on this. (Manchin has since become an independent and will be leaving the Senate in 2025.)

My intuition is that taxation on wealth will likely take the place of taxation on corporations in the upcoming tax debates, especially as outsized figures like ultra-billionaire Elon Musk take center stage in politics.

This is also a fraught path for Democrats, but for different reasons. Taxing wealth makes intuitive sense to people, but it faces massive challenges in implementation. And the Supreme Court seems ready to knock down many forms of wealth taxation as unconstitutional, leaving few options for new taxes. If Democrats want to look in this direction to fund their agenda, they will need to plan carefully and consider the pitfalls.

This isn’t an entirely theoretical discussion. Republicans will try to extend the TCJA entirely on their own, but they may end up needing a few Democratic votes to get it past the finish line. Either way, the party will need to figure its own plan to push for as an alternative.

And with rumors circulating that Trump and Congress will ultimately opt for a short-term extension, perhaps for only 4 or 5 years, Democrats may get their chance to enact their preferred changes to the system sooner than you’d think. Democrats will almost certain gain grounds in the 2026 midterm elections, probably enough to recapture the House of Representatives.

For years, the taxation debate has been fought on rather simplistic terms, with Republicans claiming they can pay for everything they want by trimming “waste, fraud and abuse,” and Democrats promising unlimited revenue gains by taxing “the rich.” But those debates are about to get much more complex and real, as Congress begins one of the most crucial years for taxation in its history.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

A message from Exactera:

At Exactera, we believe that tax compliance is more than just obligatory documentation. Approached strategically, compliance can be an ongoing tool that reveals valuable insights about a business’ performance. Our AI-driven transfer pricing software, revolutionary income tax provision solution, and R&D tax credit services empower tax professionals to go beyond mere data gathering and number crunching. Our analytics show a company’s tax position impacts the bottom line. Tax departments that embrace our technology become a value-added part of the business. At Exactera, we turn tax data into business intelligence. Unleash the power of compliance. See how at exactera.com.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- Like most of Washington, I spent Friday following updates from Congress about whether or not the government would stay funded. These kinds of standoffs happen so often, you learn how to take them in stride–but for a while it seemed like the unthinkable, a shutdown over Christmas, could actually transpire. Ultimately, as (almost) always happens, they reached a deal to keep the federal government open until March. The original government funding bill included a one-year delay of the Corporate Transparency Act, but it was nixed from the final version. (The CTA, which requires anyone who owns a corporate entity to report who the “beneficial owner” is, has been delayed by a Texas court in the meantime.) But the final “continuing resolution” did continue to hold back $20 billion in new funding for the Internal Revenue Service which had originally been appropriated by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, to enhance the agency’s enforcement efforts. This seems to be a harbinger of continued freezes or cuts to the agency in the years to come, which would in turn scale back some initiatives to collect more from wealthy taxpayers, including those with foreign holdings. On the other hand, Democrats will no doubt fight to keep that funding in place, and Republicans will be desperate for revenue (which that funding does create.) So it’s one chess piece in a much larger game.

- As regular readers of this newsletter no doubt know, the other part of the OECD’s Two-Pillar project, Pillar One, is largely dead. I included the qualifier "largely" because part of it, Amount B, seems to have already become part of the international tax landscape. For instance, last week the U.S. Treasury Department issued a notice of proposed regulations creating a safe harbor to use Amount B calculations, which apply to marketing and distribution functions. (It’s ironic that this would be an optional safe harbor, since one of the U.S. demands that’s holding up Pillar One overall is that Amount B be a mandatory part of a treaty to implement Amount A–I’m still wrapping my head around that.) Additionally, the OECD last week released new “tools” to help with Amount B calculations. That Amount B will continue to be part of transfer pricing and international taxes is a given at this point–the remaining question is whether it will grow beyond those select activities. Time will tell.

- One under-discussed development in the international tax picture is Australia’s enactment of public country-by-country rules, likely the most robust in the world, that would apply to anyone doing business in the Land Down Under. Passed last month, the regime isn’t quite a full country-by-country reporting system, only applying to a select group of countries. The Australian government finally released the list of jurisdictions last week. It resembles any number of “blacklists,” with the usual alleged havens along with a few interesting additions, like Singapore. So while the law won’t require companies to reveal their entire operations, they will have to report income, taxes, and other items if they operate in those jurisdictions. It’s sort of a questionable subsidiary reporting requirement, in keeping with Australia’s overall approach of highlighting risky structures and subjecting them to increased scrutiny. But as this will also be public, it could have repercussions far beyond Oz.

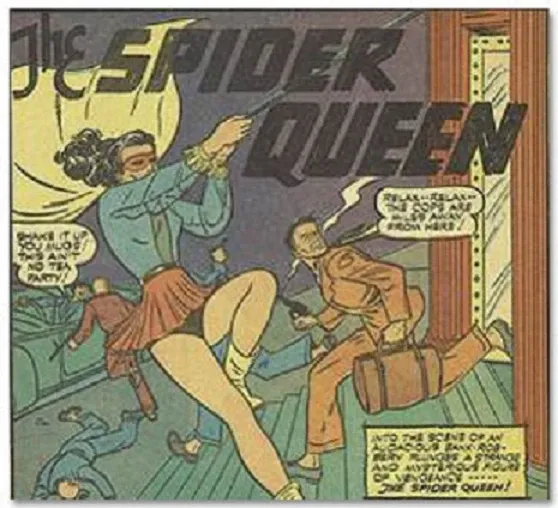

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Every week, a new character from the Golden Age of Superheroes who's fallen out of use.

The Spider Queen, first appearing in The Eagle #2 in 1941. A widow to a murdered government scientist, she learned that her husband had been working on creating "spider-web fluid" strong enough to support a person. She created special bracelets to deploy the spider-webs, and created a super-heroine persona to enact revenge on her husband's killers and evildoers everywhere. She sounds...suspiciously similar to a certain teenaged superhero who would appear decades later, sans mini-skirt.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.