The Great Unknown

Those hoping to plan for the second Trump era in international taxes can't do much more than guess.

“Nobody knows anything” is a mantra in Hollywood coined by famed screenwriter William Goldman, writer of every journalist’s favorite, “All the President’s Men.” (And graduate of my alma mater, Oberlin College.) It means that even the most seasoned and savvy producers or studio heads have no idea what will happen when a movie hits the multiplexes.

What’s true in Tinseltown is also true in D.C. Nevertheless, many lobbyists and consultants make a living doing their best to guess what’s on the horizon. If you don’t know what’s going on, you might as well not know for hundreds of dollars an hour.

But even by the usual standards of Washington chaos, Donald Trump’s second term as president has an unprecedented level of unknownability–especially in the tax sphere.

Over the past month, everyone has been asking–what will the election mean for the global minimum tax? What will it mean for digital services taxes? What will it mean for enforcement? And the answer is always the same–nobody knows anything.

Those hoping for some insight from former U.S. Treasury Department official Chip Harter, who led negotiations with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development under Trump the first time–during the first phase of the Two-Pillar project that became the global minimum tax–were in for disappointment.

“I have no idea,” Harter said, speaking at a D.C. conference held by Caplin and Drysdale and the International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation (IBFD).

His best guess was that whoever is making the decisions, it likely won’t be Trump or part of his upper level of advisors.

“I do tend to doubt that the second Trump administration would just have the bandwidth to pay attention to OECD and [United Nations] negotiations for the first year,” Harter said. “They've got so much other stuff on their agenda, God help us, that I think that they simply would not have the bandwidth to pay much attention to that.”

Unless, he added, either of those organizations do something that would ignite the White House’s ire.

That Trump will be focused on other things means that the U.S. posture towards Pilllar One or Two could be determined through the administration, which was famously chaotic during his first term. It also will likely hinge greatly on who Treasury Secretary nominee Scott Bessent picks for key political positions in Treasury, and so far he hasn’t done much to show his hand.

The possibilities under Trump regarding the OECD negotiations range from fully walking away from the process (and enacting retaliation against countries who use Pillar Two to tax U.S. companies), to Trump unexpectedly playing the dealmaker and bridging the wide current gap between the U.S. and OECD standards.

How either of those processes could play out is unclear, however. If the Trump administration takes a totally hostile approach to Pillar Two, it could mean enacting traditional tariffs against OECD nations, or turning to seldom-used provisions in current law allowing Treasury to respond in kind of it determines there is anti-U.S. discrimination. There are murmurs that Congress might enact legislation giving Treasury additional powers to retaliate against countries using the undertaxed profits rule, Pillar Two’s primary enforcement rule–likely including it in legislation to extend the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

That legislation may not even be necessary, but Republican lawmakers are eager to make a clear statement against the OECD process. (They’re also desperate for new revenue to cover the TCJA extension cost, although it’s unlikely that retaliation legislation would raise much. There hasn’t been an official estimate yet, though–so technically no one knows.)

If Trump is going to be as hardline on trade as he’s promised—enacting universal 10% tariffs, at least, to boost the U.S. economy and raise revenue—it could dilute the power of retaliatory measures on any particular country following the OECD guidelines. (Or, for that matter, countries which have enacted digital services taxes, disproportionately hitting U.S. companies.)

On the other hand, many expect that Trump may focus on enacting new trade barriers on particular nations—like China—rather than indiscriminately targeting everyone. If businesses truly believed he’d choose the latter path, the stock market response to his election would have been remarkably different. In that scenario, an individual measure on taxes might matter—or even the threat of one could provoke a response.

Of course, on the matter of Trump's true approach to trade, no one really knows what's bluster and what's real.

"I don't think anybody knows, including Trump, whether we're going to have tariffs," said New York University professor David Rosenbloom, also speaking at the IBFD conference. "Because talk is cheap."

If a deal with the OECD is in the offing, that would be an unpredictable path as well. The last time the Trump administration negotiated with the OECD on taxes, the process went off the rails late in 2019, when the U.S. switched positions and demanded that more of the policy be an optional safe harbor, rather than a requirement. It’s not totally clear what provoked the change, but it seemed to be a reflection of the impulsive nature of the Trump White House.

It’s always possible that the Trump Treasury could find some common ground with the OECD on expenditure-based tax incentives, removing one of the primary areas for potential disputes. And while the probability that the U.S. could rejoin the Pillar Two coalition under Trump is very, very low, I wouldn’t say it’s impossible. Congress, as I mentioned, is desperate for new revenue, and if Trump the Dealmaker could claim ownership over the proceedings and declare victory, the TCJA extension could include changes to conform to the Pillar Two framework.

Hey, anything’s possible.

But there are further unknowns here. Even if Congress changed course on Pillar Two, it’s very unlikely that it would enact the entire policy. It would probably make some changes to the existing U.S. minimum tax regime, the tax on global intangible low-taxed income, and request OECD nations to grandfather the U.S. into the system and declare it compliant, turning off potential enforcement taxes. But would the OECD ever agree? Would Congress, not knowing if it would be enough, enact those GILTI changes? Could the OECD provide an assurance before those changes are passed, and would Congress ever take that assurance seriously?

There is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the TCJA extension in general. But that’s at least within the realm of normal D.C. uncertainty in the legislative process. Both the cost and the length of the extension are in flux. (The two are connected—lawmakers are considering a shorter extension to keep down the bill’s cost, at least on paper, to get all of the Republican razor-thin majority on-board.)

All of this uncertainty doesn’t necessarily mean anything, other than exasperation among the financial accountants who must estimate potential tax liabilities for future years. And perhaps a reduced flow of investments due to concerns about the lack of stability.

And it’s certainly not good for policy when there are this many unknowns. Is this the dawn of a new era of tax cooperation, or will such dreams evaporate amid a retreat to protectionism and unilateralism?

The answer, of course, is that nobody knows anything.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

A message from RoyaltyStat:

RoyaltyStat® is the market leader in databases of royalty rates and service fees from third-party transactions to facilitate transfer pricing compliance and the valuation of intangibles. Our focus on high-quality data, unique transfer pricing analytics, and knowledge-based customer support makes us the choice of transfer pricing practitioners worldwide, including the top accounting and law firms, Fortune 500 multinational entities and more than 15 tax administrations. Find out more at royaltystat.com.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- The Internal Revenue Service touted new revenue it has brought in from initiatives allowed through the funding boost in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. This includes $1.3 billion from delinquent wealthy individual taxpayers (doubtlessly including those with international holdings) and $2.9 billion from criminal enforcement in tax and financial crime, including "drug trafficking, cybercrime and terrorist financing." Obviously this doesn't come in a vacuum--the incoming Trump administration and new conservative majority in Congress has vowed to freeze or reduce the agency's funding, and Trump wants to replace current IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel with a partisan congressman who is no doubt skeptical of these new IRS gains. This issue has even become a sticking point in negotiations over how to continue government funding through December and into the new year, even before Trump takes office. The agency also notes improvements in customer service through the "Digital First Initiative."

- The concept of tax morale--public willingness to pay taxes, beyond enforcement--has long been a subject of fascination for me. Since every tax authority has resource restraints, all tax systems require some degree of voluntary participation. Why some people tend to follow the rules, while others don't, explains a lot about the overall cohesiveness of the state and whether citizens view the government as a vehicle for shared responsibilities, or just the authority legally authorized to use force. (Somewhat counterintuitively, the United States has very high tax morale--we may complain a lot about taxes, but most of us want to pay them and move on.) The OECD last week published a brief report on public trust in taxes, focusing on Latin America but including global data as well. Perhaps not too surprisingly, it found signs of increasing cynicism about their own experiences with tax authorities, although there is still strong support for the principles of taxation in abstract. Another interesting finding--gender, often a solid indicator of tax morale, was only a small factor in this survey.

- Another subject of interest to many developing countries--taxation issues in the mining sector. The OECD last week released a "draft toolkit" on "ring-fencing mining income," or setting up special rules for mining companies in response to delayed tax payments due to the huge deductible costs a mining conglomerate can record in a single year. The document notes positives and negatives for this approach. The OECD is seeking public comments on the toolkit before Jan. 31.

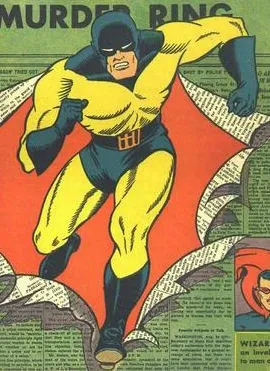

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Every week, a new character from the Golden Age of Superheroes who's fallen out of use.

The Black Hood, first appearing in Top-Notch Comics #9 in 1940. A police officer who was framed, disbarred, shot and eventually left for dead in the woods, Kip Burland was healed by a mysterious hermit who eventually trained him in the superhero arts. He cleared his name against the criminal mastermind who framed him and came to lead a double life as a cop and vigilante. Black Hood also became a pulp novel and radio star--and lost the secret identity and superhero garb, instead working as a private detective.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.